"Liberation is an inevitability of life, from Palestine to Beijing, and onward to the whole world"

Discourse Power | June 26, 2025

Greetings from Jerusalem,

On June 14, Xue Jian, the PRC Consul General in Osaka, Japan, shared a graphic on X comparing the State of Israel to Nazi Germany. The table included parallels such as:

"The Nazis persecuted Jews" vs. "The Jews persecute."

"We are a sacred, chosen people."

"Invest most of their national resources in the military."

"Ignore international law."

"Settle on conquered lands."

"America is the enemy" (for Nazi Germany) vs. "America is an ATM" (for Israel).

Israeli Ambassador to Japan, Gilad Cohen, swiftly condemned this as “shameful incitement,” antisemitic, and an offensive trivialization of the Shoah (Holocaust).

The inflammatory post emerged amidst heightened tensions between Israel and Iran following 18 months of conflict involving Hamas and the rest of the Iran-backed “Axis of Resistance”.

Following the Hamas massacre on October 7, 2023, and the subsequent Israeli military campaign in Gaza, there has been a global surge in anti-Israel and antisemitic sentiment, and China is no exception.

Unfortunately, it came as no surprise that PRC officials, state-run media, and tightly controlled social media under CCP oversight disseminate antisemitic narratives aimed at demonizing and dehumanizing the Jewish State. This trend has been visible for several years and has grown significantly as a function of China's deteriorating relations with the United States and the West and the ongoing war.

Consul Xue Jian, in particular, has persistently propagated pernicious antisemitic tropes, both before and after recent conflicts, notably comparing Jews to war criminals of the Japanese Imperial Army (from his base in Osaka!) and describing them literally as "baby-devouring demons."

Xue’s tweet was later deleted, while the Chinese Embassy in Israel provided no explanation or comment, but I find some solace in knowing that blatant acts of antisemitism continue to be a source of embarrassment in most civilized societies.

My deeper concern lies elsewhere. Dara Horn, in her 2021 book People Love Dead Jews, highlights how contemporary antisemitism, especially prevalent in certain cultural and academic circles on the left, often cloaks itself in moral or social justice rhetoric. She argues this subtle, institutionally-sanctioned antisemitism is particularly insidious, encapsulated by her point: "The most dangerous antisemitism is the kind that sits on your bookshelf."

Horn's warning came to mind as I read Professor Yin Zhiguang's recent peer-reviewed essay, which we present in full translation below. Yin is a faculty member in the Department of International Politics at Fudan University’s School of International Relations and Public Affairs.

Yin's article, titled Liberating the Mind: The Dual Mission of Cultural Decolonization in the Global South 解放心灵:全球南方文化去殖民化的双重使命, was recently published in the Spring 2025 issue of Eastern Journal as part of the special feature "The Cultural Dilemmas and Future of the Global South."

The translation is accompanied by an introductory analysis written by my senior colleague, Dr. Shalom Salomon Wald.

Shalom was born in Milan, Italy, on May 6, 1936, and grew up in Basel, Switzerland, surviving the Shoah and the war. He studied social sciences, history, and religious history, obtaining his PhD from the University of Basel in 1962, and worked for four decades with the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD).

Since 2002, he has been serving as a Senior Fellow at the Jewish People Policy Institute (JPPI) in Jerusalem, where his research focuses on Jewish civilization and people-to-people ties with major Asian powers. His notable works include China and the Jewish People: Old Civilizations in a New Era (2004), Rise and Decline of Civilizations: Lessons for the Jewish People (2014), and India, Israel and the Jewish People (2017).

His forthcoming paper, which examines the origins and intentions of Chinese manifestations of antisemitism, will soon be published on www.jppi.org.il.

Thank you for reading,

Tuvia

A Note on Yin Zhiguang’s “Liberating the Mind”

by Dr. Shalom S. Wald, JPPI

Yin Zhiguang, a Professor of International Relations at Fudan University in Shanghai, advocates global “cultural decolonization” and strengthening the China-led Global South. His Marxist-Leninist rhetoric and Maoist appeals to the Third World appear to align closely with President Xi Jinping’s ideological framework.

While Yin consistently denounces the United States, the only other Western nation facing comparable criticism from him is Israel. According to widely accepted definitions, he expresses antisemitic views by applying unique double standards to Israel, suggesting global Jewish influence behind alleged misdeeds, and condemning Israel for actions also attributed to China.

In recent interviews, Yin has identified pivotal moments that shaped his political consciousness. For instance, the widespread anti-Chinese protests originating in Tibet in 2008 profoundly unsettled him. Equally disturbing was the inhumane exploitation he witnessed as assistant professor at Zayed University in the UAE, where impoverished Egyptian, Jordanian, and Yemeni laborers suffered severe mistreatment. However, neither Tibet nor inter-Arab exploitation involved Israel or Jews.

His reaction to Israel’s September 2024 pager attack against Hezbollah terrorists was revealing: “How dare the West speak of civilization? Israel’s atrocities reveal that Western civilization has never had a moral bottom line.”

This statement reflects a broader conflation in the Chinese imagination between the West and the Jews. Two decades ago, young Chinese generally admired Western civilization, and particularly American culture, and often associated Jews positively with Western intellectual and economic achievements.

However, the US-China trade war (2018) and subsequent diplomatic tensions significantly eroded perceptions of the West in China, impacting views of the Jews by extension. The Gaza wars (2021, 2023-5) provided China with additional opportunities to criticize the United States and Israel.

Yin’s accusations are at times exaggerated and unsubstantiated, such as asserting that “Israel has deliberately assassinated countless Palestinian poets.” He also described Israeli Jews as their parents’ Nazi prosecutors, the “armed guards of Gaza’s open-air concentration camp.”

It is unlikely that Yin has visited Gaza, and such claims could reflect an attempt to deflect attention from human rights criticisms against China: The Cultural Revolution-era mass persecutions and recent internment camps for Muslim Uyghurs.

At the end of the article, Yin emphasizes historical allegations against Israel: “Israel’s colonial rule over Palestine has lasted 77 years,” implying Israel’s creation in 1948 was inherently illegitimate.

In an article he published less than two weeks after the October 7 massacre, he claimed, “Israel’s regime is both an outpost of a contemporary capitalist global empire and a time-capsule of the 19th century capitalist colonial empires.” This echoes slogans familiar from Western anti-Zionist discourse.

Yin further asserted that Western criticism of Israel is silenced by financial capitalists...a shadow empire”, referencing antisemitic tropes about secret Jewish influence.

Yin manipulates Chinese history as he does Jewish history. He writes that in 1958, “China launched a rapid campaign of cultural decolonization”, requiring “the stimulus of new ideas,” but omits that Mao Zedong’s Great Leap Forward, initiated the same year, resulted in tens of millions of deaths due to forced industrialization and collectivization. He inaccurately claims: “China has never been alone in this world...always a member of the Afro-Asian nations,” overlooking China’s centuries-long self-imposed isolation since the Ming dynasty.

The author exemplifies trends in Chinese academia under Xi Jinping’s prolonged rule, where historical narratives are frequently distorted, a common practice among Communist Parties since Lenin.

It is unclear if Yin influences Chinese government positions or widespread antisemitism in Chinese social media. While China lacks deep-rooted historical antisemitism, Yin obtained his Ph.D. from the University of Cambridge in 2011, where, in 2024, some students now openly demonstrate support for Hamas, calling for “intifada until victory,” and threaten their Jewish classmates.

These ideas from Western campuses may have resonated within China's elite universities, illustrating antisemitism as a cultural phenomenon spreading from the West to China.

“The ‘link’ is, in essence, a question about world order”

In many contemporary Western discussions on decolonization, “colonialism” is often regarded as a bygone policy. As a result, resistance to colonialism tends to be treated more as an emotional or scholarly reflection on history. Few discussions consider “decolonization” as an ongoing, holistic, and practical exploration of a more equal world order.

In reality, if we understand colonialism as an endogenous phenomenon in the formation of the global capitalist market, and consider the hierarchical political order it sustains, as well as its machinery of violence, to be integral components, true "decolonization" does not end with the abolition of colonial policies. Rather, it becomes a long and arduous process undertaken by formerly colonized peoples. Through post-colonial state-building, they struggle to liberate their socioeconomic, political, and cultural systems from the oppressive structures and mental frameworks established by colonial globalization.

Only from this perspective does the discussion of “decolonization” gain clear relevance to the present and the future. Within this protracted and systemic political, economic, and cultural decolonization process, China is undeniably a member of the Global South. It participated in post-World War national modernization efforts and solidarity movements under the banner of the "Third World." These endeavors have contributed to a shared, forward-looking significance in the pursuit of a more equitable global order.

In Black Skin, White Masks, Frantz Fanon writes that the Black person “has two dimensions”: one is “the link he shares with his fellow men 同胞,” and the other is “the link with the white man” (1). Here, Fanon identifies the enduring oppression exerted by colonialism as ideological hegemony over the colonized. This oppression does not disappear with political decolonization; on the contrary, the colonized often strive to become someone else: “to become identical to the colonizer.” Alternatively, the colonized attempt to essentialize their own culture by romanticizing everything from the precolonial era as a net positive.(2)

However, neither of these ideological fantasies truly connects with “one’s fellow men”; they fail to relate to the living reality of those who now exist in a world irreversibly shaped by past colonizers.

The question of how to think about the “link” is, in essence, a question about world order. Whether it is the desire to become the colonizer or to aspire toward the image of the colonizer, these expectations are based on preconditions of a hierarchical and elitist vision of the world. This hierarchy is pervasive, yet it has been imposed by colonizers using frameworks such as natural law, moral codes, theories of civilizational hierarchy, determinism, and atomistic worldviews; all are forms of knowledge that claim to reflect universalism and have come to dominate our conceptual space.

The subject engaged in this form of imagination longs to become a “better” version of themselves. But this “better self” is not truly about being connected to the world; instead, it's an aspiration to extract oneself, and only oneself, from present circumstances. For many of the colonized, this “extraction” resembles a substitution: replacing the former colonial elites with a new set of elites, without dismantling the hierarchical order of colonialism. This mode of imagining the world, a psyche cut off from others and historical “connection”, traps everyone within the epistemological shackles 认识论枷锁 forged by colonialism.

It is within the realm of “culture” that we find a crucial space for rethinking what true universal liberation means, and for breaking free from the epistemological chains of colonial imperialism.

I. Introduction: A Guide Through Overlapping Meanings 导重叠的意义

Time and space of the living and the dead, past and future, here and there, us and them can overlap within a single sentence. All uncertain possibilities and undiscovered causal relationships can collapse in an instant. This is the power of language.

In October 2015, Palestinian poet Dareen Tatour wrote:

Resist, my defiant people قاوم يا شعبي الثائر

Write me as prose upon agarwood واكتبني نثراً في الندّ

For you have become the answer to my remains. (3) قد صرتَ الرد لأشلائي

[The original poem also includes these lines, which Yin omitted:

I will not accept the peaceful solution لن أرضى بالحل السلميI will never lower my country’s flag until I lower them down (i.e., expel Israelis/Jews) from my homeland لن أُنزل أبداً علم بلادي حتى أُنزلهم من وطني

Resist the settler’s plunder and follow the caravan of the shahids قاوم سطو المستوطن واتبع قافلة الشهداء. [martyrs, i.e., Palestinians killed in confrontations with Israeli forces, inluding terrorists and civilians, are often called shuhada]

Resist the oppressor colonizer قاوم بطش المستعمر

Don’t listen to the [Palestinian] lackeys who have bound us with the illusion of peace لا تصغِ لا تصغِ السمع لأذناب ربطونا بالوهم السلمي

As we read this poem here and now, Israel's colonial rule over Palestine has lasted 77 years. Over 77 years, the lives of our grandparents, parents, and those of ourselves, and the younger generation have undergone tremendous changes. Yet Dareen and her people seem frozen in a cruel temporal void, enduring a life cycle filled only with bloodshed and repetition, without a future. The force that created this temporal void is veritably real.

Because of this poem, Dareen was imprisoned by Israeli authorities. She was 33 at the time. The poem, titled Resist, My People, Resist Them, commemorated 18-year-old Hadeel al-Hashlamoun, who was shot dead by Israeli soldiers at Checkpoint 56 on Martyrs’ Street in Hebron on September 22, 2015. In her bag were a phone, a pen, a brown pencil case, and some personal items - these items triggered the metal detector and, and, in broad daylight, the soldiers murdered her. [An IDF probe found al-Hashlamoun wielded a knife while walking to the soldiers at the checkpoint and was shot after ignoring warnings. You can watch the photos from the incident here.]

Hadeel’s fate is a daily reality for Palestinians. On the same day, Israeli soldiers opened fire on crowds at other checkpoints in the West Bank. [It's unclear which cases he is referring to. According to available records, the only other fatality that day was a 21-year-old Palestinian man who, according to Palestinian sources, was shot by Israeli troops. The IDF reported that he was killed by an explosive device he intended to throw at troops.]

Beyond physical elimination, Israeli authorities have systematically silenced Palestinian voices. Since the massacre on October 7, 2023, Israel has deliberately assassinated countless Palestinian poets [there is no evidence that Israel carried out a systematic campaign to assassinate poets]. In stark contrast, Palestinian poetry, prose, songs, novels, and plays have increasingly become weapons of resistance, like stones, daggers, and rifles in the hands of Palestinians. On occupied land, amid the ruins left by bombings, Gazans gather to recite poems of resistance. (4)

[A "massacre" did occur on October 7 during the Hamas-led invasion of Israel, when approximately 6,000 Palestinian terrorists breached the border carrying very real “stones, daggers, and rifles,” as well as RPGs, drones, hand grenades, among other weapons. Around 1,200 Israelis and foreign nationals (including at least 4 Chinese), mostly unarmed civilians, were murdered, raped, or burned alive, and about 250 were taken hostage. 58 hostages have remained in Gaza for over 600 days. All but 20 were murdered in captivity.]

At these gatherings, people commemorate the dead by reading their poetry, and remembrance becomes a form of struggle. Among these poets, Heba Abu Nada’s work is often cited. On October 8, 2023, she wrote on social media: “The missile’s tail flare is Gaza’s only light in the dark [of] night, the bomb’s roar the only sound in Gaza’s stillness. Prayer is the only solace in fear, martyrs the only radiance in the dark. Goodnight, Gaza.” (5) Twelve days later, she was killed in an Israeli airstrike. Among her many works, the short poem Pull Yourself Together stands out:

So wipe away فامسح

Your old and new poems قصائدك القديمة والجديدة

And the crying والبكاء

And pull yourself together, O country وشدي حيلك يا بلد (6)

Indeed, if poetry were the oppressed’s only language, it would be meaningless. Only when tied to the goals of a larger community can it become a weapon for those active, the starting point of an awakening of the consciousness of subjectivity 通往主体性意识觉醒的起点. In this sense, the resistance conveyed in today’s Palestinian poetry must be understood as part of a longer, broader anti-imperialist, anti-colonial historical process.

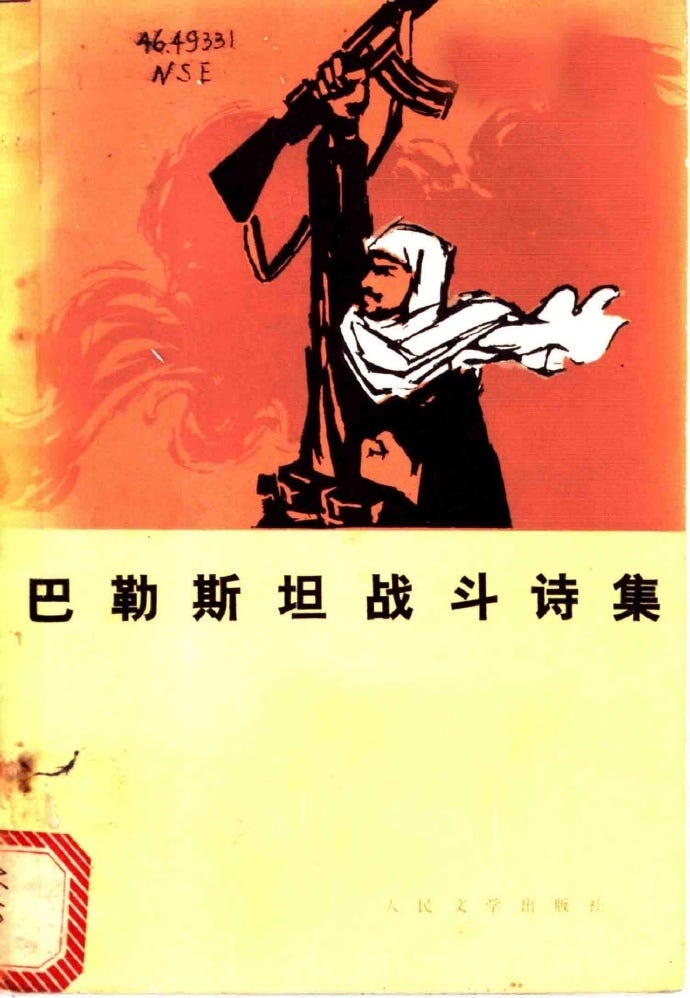

In 1975, shortly after the Fourth Arab-Israeli War, [Yom Kippur War, which began on 6 October 1973, when a Pan-Arab coalition led by Egypt and Syria invaded Israel] the People's Literature Publishing House in China edited and published Poems of Palestinian Struggle 巴勒斯坦战斗诗集. In the preface written by “workers of the Beijing First Machine Tool Plant,” the poems were praised for “overflowing with... the spirit of struggle 斗争精神,” and were described as “lines dipped in fire and blood 蘸着火和血的诗行.” Reading the collection, they wrote, “further strengthens our militant solidarity with the Palestinian people” and enables “us to join the Palestinian people, the peoples of Arab countries, and all peoples of the world in opposing imperialism, colonialism, and hegemonism, and working together for the advancement of humanity.” (7)

The war poetry written by Palestinian guerrilla fighters was translated into Chinese, compiled into a collection, read by workers in Beijing, and commented on in long-read essays. This process went beyond the familiar realm of cultural and intellectual production. The participants in this global intellectual activity were not part of a specialized society of men of letters (“Une Société de Gens de Lettres”). Literature was not their main occupation. Rather, it resembled a sacred experience grounded in reality, linking them across time and space to Palestine and the global anti-colonial movement, endowing the sacrifices of a people with broader and more universal meaning.

These guerrilla poems were only one part of the broader worldview of ordinary people in the 20th-century New China [=the PRC]. Following the Bandung Conference in 1955, a wave of cultural exchange and cooperation across Asia, Africa, and Latin America began, to expose and resist colonialism and imperialism. In the following decades, historical records, literature, travelogues, and biographies from these regions were widely translated in China. This responded to Bandung’s call to strengthen cultural cooperation among Asian and African nations. The cooperation was not purely spiritual: “cultural exchanges should respect the development of each country’s and people’s culture... to facilitate mutual learning and emulation,” and through cooperation, ultimately overcome economic and cultural backwardness.(8)

In 1958, Asian and African countries held a Writers’ Conference in Tashkent, explicitly setting out the cultural liberation task of “eradicating the poison of vulgar imperialist culture, establishing new national cultures, and making each nation’s traditions a shared artistic treasure of humanity.” (9) In this real mission intertwined with national liberation, poets were regarded as “the conscience of the people,” bearing responsibility not only for “the fate of their contemporaries, but also for that of future generations.” (10)

II. Change of the Heart: The Long Journey from the Ideal to Reality and Toward the Future

In the context of Third‑World cultural cooperation, China’s practice conveys the ideal of a holistic and equal modern world order. Internationally, this ideal reflects dissatisfaction with the unequal structure of the existing capitalist global market. It calls for a tangible disruption of that framework through self-sufficient development, starting with the vast regions of Asia, Africa, and Latin America, the weakest links in the global capitalist structure. Domestically, it involves an ongoing pursuit of a better life for the broad masses and, under the leadership of a Marxist vanguard party, the mobilization and transformation of existing social and cultural resources to awaken genuine popular consciousness.

The effort to overhaul unequal orders at home and abroad , both in principle and in practice , centers on cultivating autonomous consciousness among the people. This process builds on extensive cultural empowerment and aims at tangible socioeconomic development. It strips away the mysticism and conservatism within inherited cultural achievements that safeguard hierarchical clan orders, fuses them with basic material aspirations, and converts them into a public will that upholds public morality and ethical order. That public will, in turn, can energize materially autonomous development amid modernization.

This long road toward “complete political, economic, and cultural independence” is, in China’s view, the historical march toward “the independent emancipation of the peoples of the world.” (11) Along this road, the “anti‑imperialist, anti‑colonial peoples” unite “like brothers” based on equality; mutual assistance is not only a moral imperative but also an essential practical means of overcoming the many difficulties encountered in practice. (12)

In the mid-twentieth century, during the first wave of national independence movements across the Third World, an obvious but often overlooked question in positivist research emerged: where did the confidence to achieve decolonization and national independence come from? In China’s revolutionary nation-building experience, this was expressed as the issue of "cultural liberation 文化翻身." In The True Story of Ah Q, Lu Xun eloquently illustrates the crisis of self-confidence through Ah Q’s submissive deference 唯唯诺诺 to the structural hegemony of village feudalism, and his instinctive reproduction of that same oppressive logic when power momentarily shifts in his favor.

In his detailed account of the Zhangzhuang land reform in Changzhi city, Shanxi, William Hinton 韩丁 noted that the oppression by landlords over peasants involved not only political-economic structural forces but also the control of public opinion in the name of “tradition.” This epistemic power led people to believe that “the more land, the better... obtaining land was seen as a just reward for virtue.” Possession of wealth thus became “proof of moral superiority.” The poor “were poor simply because they were born under an unlucky star 生不逢辰.” Such “orthodox ideas” were continuously instilled through ancestor-worship rituals in village schools open only to a few, becoming “stubborn fortresses against social change.” (13)

Similarly, in many colonies, this deeply entrenched hierarchical culture also took the form of religious-like worship of the colonizer. Before the Boer War [1899-1902], examples abounded of African peoples viewing white colonizers as supernatural, untouchable “deities 天神.” But with the advent of mechanized, large-scale wars among colonizers in the 20th century, the myth started to rapidly collapse.

Of course, maintaining this myth of white supremacy was not solely reliant on transcendent religious dogma. In the memoirs of first-generation African leaders such as Kenneth Kaunda and Kwame Nkrumah, one frequently encounters accounts of how colonizers disparaged Black people’s ability to govern. The most systematic formulation of this perspective appeared in the early 19th century in Hegel’s philosophy of history. This view emphasized that Africans, due to a lack of subjective initiative, were incapable of mastering their destinies; subject to the whims of nature, Africa was deemed utterly incapable of forming modern states or creating history like Europe. As a kind of cultural branding, this epistemology, that “Africa has no history”, has never disappeared.

During a visit to the US in June 1969, Chilean Foreign Minister Gabriel Valdés flat-out told President Richard Nixon that US policy in the American trade community was hegemonic through and through. Valdés criticized his America First policy 美国优先政策 for hindering Latin America’s development and trapping it in hardship. Present at the meeting was also US National Security Advisor Henry Kissinger. At a luncheon the next day, Kissinger bluntly rebuked Valdés, saying, “Mr. Minister, you made a strange speech. You come here speaking of Latin America, but this is not important. Nothing important can come from the South. History has never been produced in the South. The axis of history starts in Moscow, goes to Bonn, crosses over to Washington, and then goes to Tokyo. What happens in the South is of no importance. You’re wasting your time.” (14)

That “the South does not make history” was not an invention of Kissinger, but the branding of a monistic worldview and global order. This worldview holds that order is created and implemented from the top down by a singular or omnipotent set of forces. The governed can never understand the powers that rule over them. These powers may be secular governments or divine rights.

This kind of monism did not vanish with the Enlightenment. Rather, under the push of its ideals of equality and rationalism, a self-possessed, spiritually cohesive, and purpose-driven group of “literati” 文人团体 gained equality before God, as if they were on equal terms with the divine. These thinkers, writers, preachers, and reformers - driven by reason and willpower - replaced the transcendental divine rights and began imbuing human action with meaning. On this self-fashioned path to glory, rationality was both the literati's motivation and motor.

The “literati” have occupied a seat of honor within the hierarchy of European society since the era of the Enlightenment. As capitalist global expansion accelerated, this hierarchy was replicated in the colonies by imperialist powers, appearing in the form of racism, elitism, and other manifestations. Within this worldview, colonizers were positioned as the sole bearers of advanced technology and culture. Colonial hegemony was thus narrated either as a “civilizing mission” with the halo of Enlightenment, or (by the mid-20th century) repackaged in classic American modernization theory. The latter emphasized that ex-colonies and semi-colonies, now referred to as "developing countries," could transition from traditional to modern societies by closely mimicking the West.

In contrast to this modernization theory, which is based on the Western Enlightenment and centered on the "literati" and capitalist elites, the modernization process that began in the nineteenth century through Third World decolonization had to answer a different question: how can the oppressed, the "ignorant," and the "proletarian" masses achieve said self-fashioned glory? On the material level, this modernization process was no different from that of the West. Specifically, it meant using modern industry, science, and technological revolution as the driving force to drastically transform traditional agrarian societies into modern industrial ones. The process entailed that industrialism penetrated all realms of economics, politics, culture, and thought, leading to profound changes in social organization and behavior. (15) Understanding how this material transformation unfolds locally under different social conditions is a shared challenge for all non-Western societies in asserting epistemic autonomy 知识自主性.

III. Transformation: Dialectics of Enlightenment and Popular Education

How can cultural emancipation 文化翻身 be achieved? Behind this question lies not only cultural policy but also a deeper inquiry into the philosophy of history 历史哲学 [a term coined by Voltaire]. In terms of cultural policy, many countries across Asia, Africa, and Latin America (including China) have recognized the core purpose of education for the masses 群众教育.

On July 20, 1948, shortly after being released from a British colonial prison, Kwame Nkrumah, the General Secretary of the Convention People's Party (CPP) of the Gold Coast, founded a school named the “Ghana College.” In his inaugural speech, Nkrumah described the fundamental task of this school as “liberating the minds of our youth 解放我国青年的心灵.” These liberated minds could “combine the best of Western civilization with the best of African culture.” As one of the few “conscious intellectuals” among “peoples under foreign rule,” these individuals could become “the vanguard of the struggle against foreign domination” and ultimately realize the goal of “establishing a free and unified Gold Coast within a United States of West Africa (USOWA 西非合众国).” (16)

Kenneth Kaunda also envisioned a “humanist education” campaign for Zambia, spearheaded by the government; it began with civil servants and later expanded to the whole population. (17) This top-down, elite-driven model became a basic framework for cultural cooperation among Asian and African countries during the Afro-Asian solidarity movement, and was reflected in the communiqués of four successive Afro-Asian Solidarity Conferences.

It is worth noting that this vanguard party model, imbued with Enlightenment overtones, acquired an additional layer of meaning in China’s political practice, that of people-centrism [minbenzhuyi 民本主义]. If we see the top-down leadership and mobilization by the vanguard party as a movement “into the masses,” then the experience “from the masses” fully turns Enlightenment into a dialectic. It is precisely through this dialectical movement of “from the masses, to the masses” that China offers a positivist answer to the question of where the independent spirit 自主精神 comes from. On this positivist foundation, the judgment that liberation will inevitably be achieved avoids becoming a hollow or transcendental fantasy, instead transforming into a spiritual will capable of motivating people to exercise their subjective initiative.

Like all colonial and semi-colonial nations, one of the key questions China’s revolution had to resolve was how to carry forward the long social revolution after completing the tasks of political revolution. The task of social revolution here is an organic part of state-building. For the vast majority of decolonized and newly independent countries in Asia and Africa, quickly cultivating a large domestic corps of civil servants, intellectuals, and economic actors capable of assuming vital responsibilities for the normal operation of the state was not only an urgent practical necessity, but also a form of social protest against the colonial political-economic order.

In contrast, the process of social revolution led by the Communist Party of China was a bottom-up outcome that grew out of the difficult political revolution and the accumulated experience of revolutionary base areas. Ideally, the vanguard nature of the party must be continuously updated in real time per the changing tasks of national development and social revolution. Before the concrete needs of the nation and state, this vanguard must act as “down-to-earth people, rich in practical spirit,” bearing the role of “guides” and “pathbreakers,” and must “lead and organize the masses” to realize the goal of enabling the “broad masses to participate” in the process of social liberation. (18)

One of the main differences between China's socialist approach to cultural education and the humanistic-oriented models of cultural education in then-newly independent Asian and African states is the combination of vanguard education and mass education, which involves bringing the vanguard party's work to the masses. In these countries, a clear rupture often emerged between vanguard enlightenment and mass education.

In terms of educational substance, another important feature that emerged in the Chinese revolution was the organic integration of nationalist demands with internationalist ideals. In China’s revolutionary practice, the reciprocal relationship between self-liberation and world liberation was an organic component of the transformation of the “people’s” worldview. This transformation of worldview was undoubtedly part of the broader movement to “transform the world.” This understanding, that transforming China and transforming the world are mutually dialectical, was fully reflected in the political practice of the Communist Party during the New Democratic Revolution in the first half of the 20th century.

In the liberated areas, for ordinary people, this process of world transformation represented a profound shift in the method of "understanding the world." Through various forms, such as public media discussions, democratic life practices, political education, and social movements, a vital connection was established between understanding the world and transforming it. This connection gave rise to the subjectivity of the people as a political subject 形成了人民这一政治主体的主体性.

In the land reform movement in the liberated areas, this transformation of worldview took shape in three concrete steps: from “political liberation” to “economic liberation,” and then to “cultural liberation.”

In this process, peasants who were once geographically marginalized and situated at the bottom of the political and economic order began to improve their economic conditions. As their circumstances changed, their understanding of the “tianxia/world” expanded. Gradually, they developed a sense of connection between their fate and broader, more abstract forms of identification, such as with “society” or even the trajectory of human political history.

Whether during the War of Resistance against Japan, the Civil War, or the subsequent period of socialist construction, this transformation of “worldview” could consistently be regarded, in terms of work methods 工作方法, as part of “mass work 群众工作.” From the perspective of guiding ideology, “mass work” was a fundamental element in fostering the emergence of “revolutionary subjective forces 革命的主观力量” and thereby “advancing the high-tide of revolution 推进革命的高潮.”

In the Chinese revolutionary experience, the notion of the “revolutionary upsurge 革命高潮” was not merely an assessment of objective conditions. It also encompassed the actions that strengthened the “revolutionary subjective forces” through broad social mobilization. For this reason, even after the heavy losses of 1927, the Chinese Communist Party still asserted that “the international revolutionary situation was favorable to the Chinese revolution.”

The theoretical basis for this judgment lay in the internal and external crises of the global capitalist order. These calamities, it was argued, “manifested even more clearly in the colonies”, particularly through the wave of revolutionary movements in the colonial world. These included the anti-imperialist struggles in Syria and Egypt, the independence movement in Morocco, major uprisings in Dutch-controlled India, India’s ongoing strikes and unrest, and the Chinese revolution. All of these were seen as evidence that “the great contradictions of world capitalism are concentrated in the colonies.” (19)

This perspective of understanding the trajectory and significance of the Chinese revolution within the broader global context of anti-imperialist and anti-colonial struggles served to link China’s entire 20th-century history of revolution and social construction. However, this abstract theoretical understanding only gained true practical significance in the political construction of later revolutionary base areas, where “bottom-up” became a foundational work principle.

In the 1938 document New Tasks of the Provincial Party Committee under the New Conditions 新形势下省委工作的新任务 issued by the Hebei-Henan-Shanxi Provincial Committee 中共冀豫晋省委, “mass work” was regarded as “the most fundamental task in establishing base areas.” It called for “mobilizing struggles from the bottom up to establish mass organizations” and “developing an education routine, self-improvement 本身工作, and organizational function through struggle,” while avoiding “top-down, coercive organizational forms and methods of mobilizing the masses.”(20)

Educational and cultural development played an extremely important role in this process of transforming the masses and promoting their “cultural emancipation.” Summarizing the experience of mass cultural construction in Jinggou Guanzhuang, Junan County, Shandong Province, Dai Botao noted: “Mass-based cultural education is not only the result of the people’s political and economic emancipation… but also develops continuously alongside political and economic progress… Whatever political and economic struggles the masses are engaged in, we need corresponding ideological education to support them… and cultural education, in turn, can take the lead and drive political and economic development forward.”(21)

This type of cultural education, which was primarily aimed at illiterate rural populations, encompassed not only literacy but also comprehensive education in areas such as society, science, and the arts. Its goal was to empower citizens to "use culture as a weapon to pursue greater liberation for themselves and the masses, and to build the New China."

When conducting mass cultural education, in addition to integrating scientific and cultural knowledge with "the actual tasks and work of the local village and region," it is also necessary to engage in extrapolation, to pursue a "ideological elevation toward understanding how, after building a new democratic state, people's lives can be enriched and production made more scientific."

One of the important tasks of cultural education is to avoid the mistake of merely satisfying the peasants' "economic demands" without transforming their "narrow view that fails to see their overall and long-term interests," and without "further raising their class consciousness." By enhancing political awareness and stimulating enthusiasm for learning, you can achieve "increased production capacity," advance the "modernization of the means of production," and "gradually modernize backward agriculture and move toward industrial civilization."

The guiding principles for this work are the integration of "minor truths with major truths", "the distant with the near," "the past and future with the present," "internal forces with external forces," and "cultural knowledge with everyday life."

Only by drawing the political, economic and cultural emanicipation of the village and region “into the consciousness of struggle for the revolutionary interests of the oppressed working people of China and the world”, by “broadening their horizons and knowledge”, and by “combining the goodness of the future society with the progress of the present over the past”, can we “raise the political level of the masses” and ensure that they do not fall “behind the progress of the objective situation.” (22)4

Following the establishment of the PRC, this approach to educating the masses by combining visions of the future with the realities of everyday life could be found in mobilization efforts rooted in the Third World internationalist spirit. Both in terms of method and political objective, forms such as public media discussions, democratic life, political education, and social movements helped to construct an imagined community of internationalists among the Chinese people. This was undoubtedly a continuation of the "cultural emancipation" movement that emerged from the liberated areas.

In 1958, China launched a rapid campaign of cultural decolonization. It recognized that the rapid development of productive forces required the stimulus of "new ideas." The Central Committee of the Communist Party of China established Red Flag, a biweekly political journal, on June 1, 1958, with this as its primary political orientation. Red Flag’s mission was “to raise the proletarian revolutionary red flag in the ideological domain” (23). As Liu Shaoqi [then Chairman of the NPC Standing Committee, later ignominiiously deposed president] stated in his work report at the Second Plenum of the Eighth National Congress of the CPC, the new era's "technological revolution" should be accompanied by a "cultural revolution" to meet the "demands" of the technological revolution and maintain forward momentum (24).

The emphasis on the development of "cultural and educational undertakings" was reflected in the allocation of actual national income expenditure. In 1952, expenditure on "culture, education, science, and healthcare" was 1.35 billion yuan, accounting for 2.2% of total national income expenditure. By 1957, this figure had risen to 2.78 billion yuan, accounting for 3% of total national expenditure (25).

Two months after Liu Shaoqi’s speech, the CPC Central Committee approved a proposal from the Ministry of Culture to reform the administrative system for “cultural work.” The proposal stated that the majority of “cultural work” should be “oriented toward the masses.” More autonomy was to be given to local governments and the general public to "mobilize the zeal of the broad masses and cultural workers," "rapidly develop socialist cultural undertakings," and to "better serve workers, peasants, and soldiers." The Ministry of Culture would only “provide ideological and professional guidance” (26). As a result, provincial and municipal governments were authorized to set prices for newspapers, magazines, books, movie tickets, artistic performances, and theater rentals. Local governments were also able to manage the operations of “regional film production and distribution companies, bookstores, and printing houses.” At the time, as part of the nationwide literacy campaign, local cultural activities developed rapidly. By 1957, the number of public libraries had increased to 400, nearly quadrupling from 83 in 1952. By 1962, there were 541 public libraries nationwide. The number of mobile performing arts troupes also rose—from 2,084 in 1952 to 2,884 in 1957, and to 3,320 in 1962. By 1965, there were 3,458 mobile art troupes, 2,943 cultural venues, and 562 libraries distributed across China (27).

The goal of this cultural transformation is to emphasize that “the proletariat must become the master of culture.” In this vision of the future, by carrying out a “cultural revolution” in a “faster, deeper, and more efficient 更快、更深入、更高效” manner, China’s working class will, in about “fifteen years or so,” all possess advanced scientific and cultural knowledge.” By then, expertise “will have become common knowledge.” There will be “millions of professionals applying their knowledge to the modernization of industry and agriculture.” They will not only be “well-versed in knowledge” but also possess an “advanced political consciousness, brimming with enthusiasm for work.” They will become “intellectuals of the working class” and “socialist laborers.” When everyone “has a high level of cultural attainment,” the living environment will become “more civilized and sanitary 卫生.” People will be “healthier,” and those “with greater athletic talent” will compete in international sports events. In the realm of culture, there will not only be more works of literature and art that “serve the working class”; more importantly, “workers, peasants, and soldiers can also become creators of art and culture.” The entire country “will become a harmonious big family.” (28)

Conclusion: From Autonomy to the Liberated Person 从自主性到解放了的人

In contrast to the PRC, the newly emerging Asian and African countries of the twentieth century faced even harsher challenges on the path to autonomy. These countries often had highly singular and dependent economic structures, closely tied to their former colonial suzerains. At the same time, their social elites were deeply colonized [in spirit]. The weak condition of their countries meant that these new nations were continually subjected to various forms of interference from the great powers, against which they were mainly defenseless. Amid the vibrant wave of national independence in the 1950s, the old imperialist hegemonic order resurfaced in the Third World through the mechanism of great power interventionism, forming an undercurrent that further undermined the ability of Asian, African, and Latin American countries to achieve true independence and strengthen their hand. Among these forms of interference, cultural intervention became a weapon frequently wielded by hegemonic powers.

In the 1960s, the US Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) actively used the American Society of African Culture (AMSAC) to carry out comprehensive interventions in African countries that had newly gained independence or were still engaged in independence struggles. In 1963, AMSAC organized a conference at Howard University in Washington, D.C., attended by many prominent leaders of African independence movements, including Oliver Tambo, Deputy President of the African National Congress (ANC) of South Africa, and Eduardo Mondlane, leader of the Mozambique Liberation Front (FRELIMO). The CIA took advantage of this conference to observe these African revolutionaries and attempted to influence the political trajectory of the continent.

In fact, the establishment and operation of AMSAC were heavily funded by the CIA. In addition to direct grants, the CIA also used foundations and charitable organizations to finance AMSAC’s activities. These funds were primarily used to support cultural and educational projects, such as organizing conferences, publishing journals, and funding research and creative work by scholars and artists. Through this financial backing, the CIA used AMSAC to gather intelligence and to exert control over Africa’s cultural development, attempting to integrate African culture into the American cultural sphere.

By supporting pro-American and “anti-communist” African cultural events and figures, the CIA sought to undermine the influence of indigenous African cultures and promote American cultural values. Moreover, the CIA also used AMSAC to shape public opinion, incite rebellions, and attempt to overthrow African governments that did not align with U.S. interests, to install pro-American regimes. (29)

To this day, the concept of "cultural emancipation" holds significance not only for the "Third World" or the "Global South." This pursuit of autonomy also represents a deeper resistance against the entrenched elitism inherent in the Enlightenment movement. In 1955, the Final Communiqué of the Asian-African Bandung Conference formally emphasized for the first time the importance of resisting imperialist "cultural repression" 文化压制 through cultural cooperation. For the many newly established nations, resisting such imperialist cultural repression had remained a central, unfinished work in their broader project of nation-building.

Two years later, in the spirit of the Bandung Conference, the Afro-Asian Solidarity Conference (AASC) held in Cairo issued a dedicated resolution on cultural cooperation. It proposed institutionalizing cultural collaboration among Afro-Asian countries as a way to break free from colonialism’s “civilizational monopoly” 文明垄断 and to establish the cultural and political subjectivity of the Afro-Asian peoples. The goal was to challenge the intellectual hegemony of imperialism and to reclaim space and autonomy for Afro-Asian peoples within the broader trajectory of human history.

This model of equal cooperation was premised on the assertion of “national culture” in the face of Western cultural hegemony. In particular, it was undergirded by the belief that “every nation, according to its characteristics, can contribute to humanity.” These national characteristics 民族特点 did not preclude universality, as the foundation of commonality lay in the fact that all peoples lived in the same era and faced the same global market and its attendant cultural pressures. At the same time, an emphasis on national identity did not entail a wholesale rejection or uncritical absorption of traditional culture. The Chinese view of 20th-century global cultural cooperation rested on principles such as “critically utilizing feudal cultural elements” and “fully harnessing cultural heritage,” integrating them with the goals and ideals of building a better social order. (30)

Thanks to the vast network established under the Afro-Asian–Latin American cultural cooperation initiatives, we have witnessed not only the flourishing of transnational interactions among non-state actors but also the blossoming of the Afro-Asian cultural sphere.

A historical review of the cultural cooperation demands within the Afro-Asian-Latin American solidarity movement is aimed at pointing toward the future. In fact, within China’s revolutionary experience lies a theoretical theme of broad significance: the idea of “liberation” as the antithesis to [Western/US] hegemony, through which the oppressed realize their historical subjectivity in the process of self-liberation. It is not difficult to see the strong resonance between this theme and the Afro-Asian peoples’ conception of “independence” as articulated during the 1955 Bandung Conference.

In the various resolutions and communiqués of the Bandung Conference, it is clear that the fundamental consensus among Afro-Asian countries at the time was that the sovereignty and independence of the oppressed should not stop at mere political formalities. More importantly, it should involve, through international cooperation, the building of economically autonomous and culturally independent modern states domestically, and the establishment of a truly democratic international order externally.

This cooperative movement aimed at liberation required, on one hand, the formation of effective governments in Afro-Asian countries, and through intergovernmental cooperation, the accomplishment of various tasks such as eradicating illiteracy, promoting basic education, public health, advancing the rights of women and children, protecting laborers and expanding health insurance, and combating racial discrimination - All are part of building strong governments and modern societies. On the other hand, it also required grassroots-level cultural and economic collaboration to promote mutual understanding among Afro-Asian peoples and to build institutional platforms that assert cultural subjectivity and economic independence, in order to counter the penetration of informational and cultural hegemony by imperialist states and the prerogatives of foreign capital.

The worldview conveyed through cultural cooperation emphasizes that a human being is not an isolated, atomized individual, but rather someone whose complex social relationships are truly interlinked through the space created by culture, connecting people separated by time and space to a broader and profoundly real community. Just as none of us has ever existed in isolation, China has never existed alone in this world. China has always been a member of the Afro-Asian nations, an inherent part of the Global South. This expresses the Chinese Communist Party’s original aspiration regarding the world order [this is a reference to Xi's dictum to the party, "never forget our original aspiration" 不忘初心].

In a reality where unequal structures and hegemonic systems still persist, our original aspiration has always been to break the existing inequalities of the world. This is not something that can be achieved overnight, nor can it emerge from a zero-sum game, and even less so at the cost of the unhappiness of the many to satisfy the happiness of the few. In the ongoing interaction with this old world and its old order, and the shared pursuit of a better global order, we explore the possibility of building a new world of our own, so that more people may believe that the possibility of a new world is always there.

Liberation is an inevitability of life, from Palestine to Beijing, and onward to the whole world.

Link: https://web.archive.org/web/20250529055347/https://mp.weixin.qq.com/s/luh41_JGZ9prGVfd6XD0uQ

Playing in the Background

Tuvia Gering is a cyber-threat intelligence analyst at Planet Nine’s Digital Intelligence Team, a visiting fellow at the Israel-China Policy Center at the Institute for National Security Studies (INSS), and a nonresident fellow at the Atlantic Council’s Global China Hub. The views expressed in this article are solely those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the positions of the author’s affiliated organizations.